At the start of 2010, FarmVille was everywhere; at the end of 2010, Minecraft dominated the conversation. The discussion of those two games, at least on the sites I frequent, had a very different tone; I believe, however, that much of those games’ successes stem from the same source, namely their strengths as guided construction games.

I haven’t played enough FarmVille to be able to really back up that claim: my beliefs about that game mostly come from looking at others’ farms, and the impression of care and crafting that they give me. So I’m going to shift focus slightly and instead talk about Social City: it was another quite successful 2010 Facebook game, based on city construction rather than farm construction, and I played it (as well as its successor, City of Wonder) quite a bit last year. My guess is that a lot of what FarmVille players find attractive is similar to what I’m going to talk about in regards to Social City, but I could be off-base.

Social City

Social City is, as the name suggests, a city construction game. You’re given an isometric grid to build on; from the construction tab in the game, you can choose streets to form the networks of your city, buildings (residential, commercial, industrial) to lay along those streets, and decorations (trees, parks, etc.) to place between and behind those buildings.

That’s the “construction” part of “guided construction game”: as to “guided”, the game isn’t a complete sandbox. At a most basic level, the buildings come fully constructed: this isn’t Lego, you can’t create brick by brick. You also don’t begin with a blank slate: instead, the game gives you a starter town with a few streets and buildings already constructed, and while you can choose to tear it down completely if you desire, you’re more likely to use it as a base of your city’s growth, pruning and editing it as necessary. In addition, not all buildings are available at all times: the game has a level-up mechanic, so you start off with access to a relatively small set of buildings, gaining access to more and more as you progress. And you don’t necessarily have access to all the buildings that you have unlocked: industrial buildings become available by growing your town’s population, which you do with a mix of residential and commercial buildings, while residential buildings require money to purchase, which you earn from your industrial buildings. (There are also buildings that are available by spending real money and buildings you receive as gifts from other players.)

And, equally important, the buildings have character: again, Lego bricks they aren’t. The game presents a unified aesthetic, and a rather charming one at that. And it’s not a static city: the buildings come with animations (kids playing in yards, conveyor belts moving in factories), and pedestrians and cars move along your streets.

The result is a game that both Miranda and I thoroughly enjoyed. We started with the default town layout, and at first built out from it somewhat haphazardly. But fairly soon the different areas of our city took on different characters, so we moved buildings and placed buildings to emphasize those roles. We’d generally level up about once per week, so each weekend we’d have a handful of new buildings to consider, deciding where they’d best fit into our city, how they suggested we should evolve our city next. I gave a tour of my city on my other blog; we really enjoyed evolving the city to get it to that point.

Minecraft

That’s Social City; now, to Minecraft. Like Social City, you’re given a relatively coarse mesh to build on, this time made out of large 3D blocks rather than a two-dimensional grid. Like Social City, you have quite a bit of freedom as to what to do with that grid, but you are also presented with a starting layout (albeit a large-scale procedurally generated one) that strongly influences your construction. Like Social City, you have access to a relatively small collection of objects with which to build; furthermore, your choice of construction is influenced not only by aesthetic considerations but also by in-game mechanics (the ability to earn coins in Social City, to defend against mobs in Minecraft), albeit not to an overwhelming degree. And, in both cases, you have to earn your building material through menial tasks (clicking on buildings, mining): they both have a strong component of what Naomi Clark and Eric Zimmerman call “The Fantasy of Labor”.

And, again, the game has its own very strong aesthetic: the blocky pixel art style that forms the world, the (at times stunningly beautiful) landscapes that the game’s algorithm generates, the animals that wander through the world, the sunsets and sunrises, the music. This aesthetic very much influences the choices that I make when building in the game.

So, as with Social City, you end up with a game that both Miranda and I have sunk countless hours into, figuring out how we want to shape our respective worlds, starting from the canvas that the game gives us and putting more and more of our decisions into it. (Incidentally, if you’d like to join us, the VGHVI plays Minecraft together on the last Thursday of every month!)

A Continuum of Construction

I do not want to pretend that Social City and Minecraft are somehow the same game underneath: there are significant and substantial differences in the world-building that the two games enable. (In particular, Minecraft provides a vastly larger canvas to work upon.) There are many many people who enjoy one of those games without having the slightest desire to play the other one, and I would never want to second-guess their decisions. But when I look into why I enjoy both games, my motivations to play each of them have a lot in common.

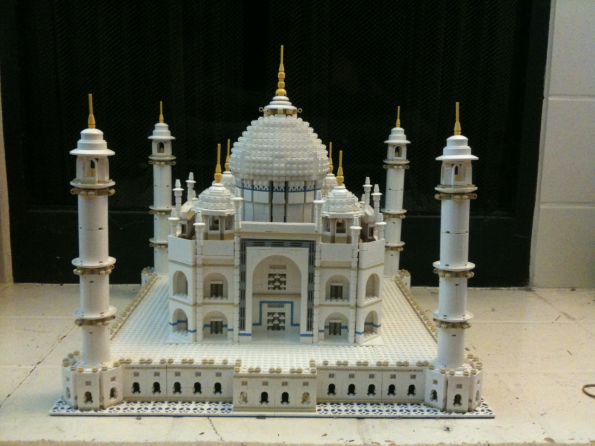

That’s perhaps clearest when I contrast them to Lego. We have a big vat of Lego blocks sitting in the house; I never have a desire to pick them up and play with them. It’s just too much of a sandbox for me: I need the aesthetic structure that Social City and Minecraft provide to give me something to work with and to base my decisions around, I even prefer the gating effect that both games’ fantasy of labor restrictions provides to having all the building blocks available at hand. (Miranda frequently plays in multiplayer mode with block creation powers available, while I only do that on VGHVI nights; I can imagine eventually switching over to preferring that mode as I get more comfortable with my designs, but I’m not there yet.) We actually have also done quite a bit of Lego construction this year, but that was done entirely within the context of a prebuilt kit of the Taj Mahal: that was fabulous, but perhaps a bit too far in the prescriptive direction for me. (Or perhaps not, I really enjoyed it!)

Returning to FarmVille: video game blogs spent a lot of time bashing it last year, bashing both the game itself and the players who play the game. If you’re tempted to do that, and if you’re a Minecraft fan, though, ask yourself first: are you sure that your motivations are so different from those of FarmVille players? We all love the story of the indie making it big, and Minecraft is a phenomenal accomplishment in many ways; but there are many routes to the pleasures of creation that it affords.

For another take on the guided sandbox that Minecraft provides, I recommend “How Minecraft taught me to dream”, from the blog Reflections.

Post Revisions:

This post has not been revised since publication.

Posts

Posts

Interesting article on the underlying similarities, particularly as someone with no direct experience of farmville. I wonder if there’s something to be said about the fight against chaos, the frontier spirit in games of this type. Does the scope for things to go wrong have anything to do with our enjoyment?

5/12/2011 @ 4:11 am

I wonder about the scope for things to go wrong, too. I actually play Minecraft in peaceful mode, and I don’t like crop spoilage in farming games. Though I accept that the former at least is a personal choice, so if other people like mobs in Minecraft, that’s awesome. (If people actively like crop spoilage on the other hand, then that’s, um, eccentric.) Which is one of the things I like about Minecraft: you can have fairly different experiences playing with mobs, playing peacefully, or playing multiplayer with the ability to conjure blocks out of thin air.

And even for me, mobs were very useful when I first played Minecraft (before I turned on peaceful mode), because they gave me a very clear goal right at the start: I wanted to survive the first night, which meant that I wanted enough resources to be able to dig a cave. And that in turn led me down the path of digging further into the ground, at which point I discovered natural caves, and so forth and so on… So, in that instance, the scope for things to go wrong certainly helped.

5/12/2011 @ 8:18 pm