The main question that I’d like to understand better in the current Vintage Game Club playthrough of Super Mario 64 is how the game fits into the taxonomy of the genre of platformers. Or, indeed, whether it fits into the taxonomy of that genre: while, at the time it was released, Super Mario 64 seemed to me like the natural transition of the genre from 2D into 3D, experience with later games has increased my appreciation of just how large a break with the platforming tradition it was.

At least, that was my theory; given that I hadn’t played Super Mario 64 since 1998, however, that theory could be complete bunk! So, with a replay of the first 30 stars under my belt, how do I feel now?

The Castle Grounds

The opening of Super Mario 64 is, to me, very telling. You’re not placed at the left end of a traditional level or on a map laid out like a game board: instead, you’re on the grounds surrounding a castle. And while you are “supposed” to head straight into the castle, I never considered for a moment starting by doing that. Instead, I wandered around here and there, climbing trees, swimming in the water, reading the signs and trying out the moves, wondering why there was an underwater door and so many underwater grates, trying to figure out if it’s possible to reach the coins that are hanging under the bridge.

And the music encourages this wandering. To me, it sounds significantly different from, say, the music in the original Super Mario Bros. The music in the original game isn’t relentless, but it’s always supporting your moving from left to right. Here, though, the castle theme starts off sounding like somebody tiptoeing around, wandering this way and that. Then, after three variants of said tiptoing, it transitions into a slightly more expansive bit, saying “wow, look at all this neat, stuff. (happy sigh)” That sequence repeats; and then, mimicking the player’s increased confidence, the theme has you wandering this way around the grounds, with a bit more purpose in your step. But still wandering: there’s not this feeling that you have a place to go, things to do. The plot may be suggesting that you should get to work rescuing the princess, but the music is happy to let you drink in the world.

There was a lot of talk about ludonarrative dissonance a couple of years ago; in its own way, Super Mario 64 exemplifies that, and I just can’t bring myself to consider that a problem. Instead, I’m going to stick with my earlier claim that musicals are a perfectly good model for video games: focus on your set pieces, and treat your plot as light scaffolding to let you hop from piece to piece, and good will come of it. And if the purpose of the opening set piece is to set the stage and motivate the entire rest of the game, then the wandering we have in the castle grounds is the core and foundation for the entire game.

The Levels

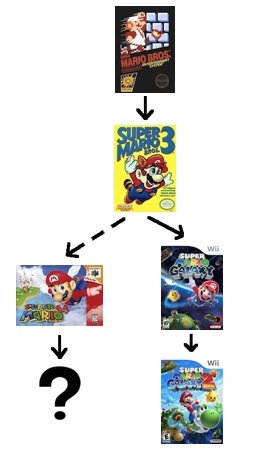

So: the opening is quite different from the 2D Mario games. It’s also quite different from the later 3D Mario games, Super Mario Galaxy 2 in particular. (Which also starts you off in an area outside of the levels that you can just mess around in; there’s surprisingly little scope for messing around, however, and it turns out that the area really primarily exists as a sort of trophy room for collecting guests.) But what about the levels proper?

They, too, have a completely different feel from later and earlier games. When I first played Super Mario 64, the levels seemed rather large to me; I was fairly sure that they’d look a lot smaller in the light of subsequent 3D games. And they are; but they’re also a lot denser than I remembered, and somehow manage to accomplish that without seeming abbreviated or cramped. Take Bomb-omb Battlefield as an example: there’s a small area at the bottom where you start, a medium size field on the right and a couple of small meadows on the left, a path that quickly spirals a couple of times around a mountain, and the mountain top that’s barely large enough for a boss fight. Yet somehow the game fits six stars in that area plus the hundred-coin star, and does it without feeling repetitive.

Ultimately, then, the core idea that I’ve gotten from replaying the beginning of Super Mario 64 is that what makes it special is the joy with which it invites you to explore a world. (I suspect the addition of the third dimension significantly affects the tenor of the experience, though I’m not sure I can justify that well right now.) And it’s a mistake to think of that as somehow inevitably tied to platforming: you can have the same feeling of exploration while driving, while leading a life of crime, while rolling around in a ball swallowing up everything in your path.

The Jumps

Having said that: while I no longer consider Super Mario 64 to be a model for a 3D platformer, and while I think it has ultimately been more influential outside of the platformer genre than inside it, diving back into the game has reminded me of how much it has to bring to platforming. Because it’s not about exploring a space in the abstract: it’s about exploring a space as Mario, as a person capable of superhuman feats of jumping. To that end, Super Mario 64 adds not one but four new moves to his repertoire: the backflip, the long jump, the triple jump, and the wall jump. I love the exploration that the game allows, and the extra moves let me travel more widely, with more choices of how I get from here to there; and one of my favorite challenges so far has been the “Wall Kicks Will Work” star in Cool, Cool, Mountain, forcing me to figure out exactly how I’ll be able to navigate my way up a series of crevasses.

In fact, this may be pointing out the narrowness of my focus: I say that those moves are new, but of course the 2D Metroid games featured wall jumping as well. And the Metroid games were about exploring environments much more than the 2D Mario games were. Though they’re much more cramped than Super Mario 64; part of that is the theme, but I’m fairly sure that a lot of that is the way 2D encourages you to fill your levels with walls if you want to combine exploration with the joy of movement. And, in a curious twist, the Metroid games shifted as much in their transition to 3D as the Mario games did; I don’t think that’s a coincidence, though I’m not sure I can justify that suspicion, either.

While I’m hesitant to label Super Mario 64 as a 3D platformer, that has more to do with the essentialist nature of labels than anything else. The game sure has a lot of platforming in it, and that’s very much a strength.

Roots and Offshoots

The title from this post came from an amusing choice of names that my computer made while copying files. But it’s curiously suggestive: the gulf between Super Mario Bros. 3 and Super Mario 64 is, indeed, rather large. There’s clearly an ancestral relationship there; but there are a lot of other connections in the family tree, and the tree continues to spread.

Post Revisions:

This post has not been revised since publication.

Posts

Posts

This article has a really interesting start. Looking closely at the design of Mario Bros. 1-3 to mark design trends to draw conclusions about the series’ jump into 3D both in Mario 64 and Galaxy drew me in.

However, this article doesn’t say much, and fails to cite strong examples for any relevant topics. There is a lack of critical-language and this in turn creates a lack of focus.

Talking about set pieces and how a game starts you off is only a neat way to transition into some clear game design analysis. Instead, you transition into talk of ludonarrative dissonance, music, moves, feelings of exploration, and level sizes. Not much was said about the core platforming challenges or how any 2D Mario game creates those challenges.

I don’t believe there is any significant ludonarrative dissonance in Mario 64 or any Mario platformer. There really isn’t enough story telling to create opportunities for such.

Perhaps the work I did here will help you: http://critical-gaming.squarespace.com/blog/2009/11/19/the-measure-of-mario-pt1.html

It’s important to have a clear grasp of game design ideas so we don’t call Mario 64 anything else but a platformer. Your primary mechanic and function is JUMP. You jump to get around, you jump to avoid enemies, and you jump to grab just about every star in the game. Talking about feelings to determine game genre can make things very difficult from the start.

10/10/2010 @ 8:10 am

Thank you for the comment and for the link to your quite interesting blog post. What I don’t understand is why I should prioritize discussion of different elements the way you do. (Which I read as: verbs are key, anything else is unimportant; and, within verbs, the important ones are those expressing direct control of your avatar: i.e. JUMP, not WANDER. Is that correct?) I can understand how, from that point of view, you would find it important that “we don’t call Mario 64 anything else but a platformer”, but as far as I can tell you haven’t (either here or in the post you linked to) given an argument why I should adopt that point of view.

10/10/2010 @ 9:35 am

I should clarify.

Verbs/gameplay mechanics are key when discussing or analyzing gameplay. Though I think interactivity and gameplay are the most unique and interesting part of video games, I absolutely love all of the other qualities like sound, music, graphics, story (I’m a creative writing major after all. Gotta love stories).

I felt that you should have focused more (or at least the start) of the discussion with verbs/mechanics because you’re talking about genre. Genre naming, though not an exact science by any means, tends to classify a game based on the gameplay. Platformer describes games where players mainly/mostly fight against gravity to navigate spaces. Shooters apply to any kind of game where you launch projectiles to win. From there things can get more specific like FPS, or SHMUPs. Still there are examples like “adventure” games where the action of “adventuring” is more vague and abstract than “shooting.”

So by starting your post by opening the topics of genre and “platforming tradition” you set up the discussion for analyzing gameplay. For Mario platformers especially, the mechanics that control your avatar are all players have. The moves are also simple (move, duck, jump, run) so there’s no need to make them more complex, ambiguous, or vague by upgrading a mechanic like move with “wander.”

Did I clear up my position?

You don’t have to adopt my critique style or my way of thinking at all. Everyone is free to tackle gaming topics how they want. I wanted to suggest my approach because I think it would really help you focus this article. The way you have it now, it’s really unfocused and doesn’t dive into enough specific details. Furthermore, using solid objective language has really helped me ground my feelings and opinions.

10/10/2010 @ 12:37 pm

Thank you for your clarification, that helps a lot. I certainly agree that this blog post would be a better one if it dived into specifics more; I’m not convinced that those specifics should have been focused on the moves, though it’s hard to say for sure without having written a more specific one! It’s certainly true that genre and mechanics are traditionally closely linked; but even if I go along with that, the implication here may be that I should talk about genre less rather than mechanics more.

Because the core idea that I was starting out with here is: to me, Super Mario 64 feels significantly different from both the 2D Mario games and the Super Mario Galaxy games. I suspect that that difference doesn’t come the move set – a slightly-more-than-cursory glance doesn’t suggest anything about the moves that points out the difference – so if I want to explore that difference, focusing on the mechanics wouldn’t be particularly productive. Focusing on areas that touch the mechanics probably would be productive – the level design, which strongly influences how you use those moves, has to be important, I think. But even there I would be wary in focusing too much on how the level design interacts with your moves, again because the moves aren’t at the core of the difference; and I’ll stand by my example of the introductory music as contributing to / reinforcing the tonal difference between Super Mario 64 and most other Mario games.

10/10/2010 @ 1:58 pm

“Super Mario 64 feels significantly different from both the 2D Mario games and the Super Mario Galaxy games.”

Best of luck to you. If you ever need someone to bounce ideas off of or help digging up examples/facts, I’d be glad to help (I gotta put my Mario knowledge to good use where I can). Sorting out one’s feelings is the goal of a critic. To quote N’Gai:

“What being a critic does is gives you access to the language to explain the gut reaction you had. And to understand it, to interrogate it, to challenge it…. My gut reaction is still my gut and that is what I trust more than anything.” ~ N’Gai Croal

When you pull it all together in writing, I hope you’ll keep me posted.

10/10/2010 @ 3:13 pm

Thanks, I appreciate the offer!

10/10/2010 @ 4:22 pm