Good Sudoku is, of course, a Sudoku app, but one that takes a rather different angle from most Sudoku apps: it wants to expose the conceptually interesting parts of solving Sudoku puzzles, instead of having you spend time on surface rules.

Some of this is done via mechanical shortcuts. Typically, a part of solving a Sudoku puzzle involves marking what the potential legal moves are for a given cell, based on the basic Sudoku rules: only allowing the numbers that don’t already occur in the same row / column / house. (A “house” is the term for one of the 3×3 groups that a Sudoku puzzle is divided into.) This is a purely mechanical operation, and a boring one; Good Sudoku gives you a single button to press to carry out this task for the entire board.

Also, once you’ve entered a number into a cell, Good Sudoku (like most other Sudoku apps I’ve used) automatically removes that number from the set of potential solutions for all the other cells that it’s connected to. But Good Sudoku goes further: for cells in the same house as the cell where you entered the solution, if there’s now only one possible number for that second cell, then Good Sudoku will automatically enter the solution for that second cell as well. This leads to a pleasant cascading effect, where entering one solution sets off a chain of other solutions; the developers decided (correctly, I think) to restrict that chain to single houses instead of the entire board, but it’s a noticeable reduction in busywork.

That’s the ergonomics of interacting with the app, removing a layer of busywork. But there’s a deeper point to this as well: Sudoku has some interesting patterns buried within it, and those patterns are a lot easier to see if you’re not spending all of your time at surface-level implications of the rules. And Good Sudoku wants to help you see those deeper patterns.

To that end, Good Sudoku has a few ways to gradually teach you about new techniques. At a given puzzle difficulty level, Good Sudoku has an explicit set of techniques that suffice for solving any puzzle that the game will throw at you. At the easiest level, those techniques are very basic: if a cell shares a row / column / house with every number but one, then that remaining number must be the value of that cell. Or if every cell but one in a given row shares a column / house with a specific number, then that number must be the value of that remaining cell. But, as you work up the difficulty levels, the techniques get quite a bit more subtle: for example, a technique called “X-Wing” says that if, for a given number and for two specific rows, and if that number only appears in two specific columns on both rows (same columns in both rows), then that number can’t show up in any other cells in those columns.

That last example sounds complicated! But Good Sudoku uses a few methods to help you learn that technique. It lets you highlight which squares can possibly contain a number, so if you’re aware of the technique, you’ve got a chance of seeing when it’s applicable. If you can’t find any way to make progress, there’s a Hint button, which will point out a technique that will help with the current state of the puzzle: it gives a description of the technique, shows you the squares that are involved, and, when you’ve carried it out correctly, confirms that you’ve done the right thing.

Also, the game tries to figure out what techniques you’re applying just by observing your actions; and, if it notices that you’ve correctly applied X-Wing three times without requiring a hint, it will congratulate you on learning the technique. And, if you like traditional book learning, there’s a technique guide available as well.

I can’t recall seeing a game that does this kind of on-demand instruction, or that deduces the intent behind your actions in this way. Honestly, a lot of human teachers don’t provide this sort of on-demand just-in-time instruction: human teachers have a habit of focusing on scripted book learning too! But Good Sudoku carries it off, and it’s very effective: I was decent at solving Sudoku puzzles before, but I’m much better at them now. Honestly, even if you don’t care about puzzles at all, Good Sudoku is well worth playing if you have any interest in computer-aided learning.

So, that’s the core of what makes Good Sudoku interesting. Now I’m going to go in a more tangential direction, though, about the nature of puzzle games.

The basic premise of a Sudoku game is simple enough: you’ve got the rules for the game, you’ve got some numbers filled in, and you want to fill in the rest of the numbers to get to a legal solution. But, it turns out that there are actually three different things that the phrase “solve a puzzle” can mean. One is “find any legal solution to the puzzle”. A second is “prove that there is a unique legal solution to the puzzle”. And the third is “assume that there is a unique legal solution to the puzzle, and find that solution”.

Temperamentally, when solving a puzzle, I’m usually going down the second route: I’ve seen puzzle games that go the first route, and they annoy me a little. Certainly in the past, when solving Sudoku puzzles, I’ve taken the second route.

I was vaguely aware, though, that there are actually techniques to solve Sudoku puzzles that go down the third route. Good Sudoku generally stays away from requiring those techniques, but if you select the highest difficulty level, then it’ll start using a technique called Unique Rectangles / Avoidable Rectangles. (Actually, it’s a family of techniques, but never mind that for now.)

So, when I made it to that difficulty level, I ended up learning Unique Rectangles. Which, in turn raises two questions: what do I think about that technique from a philosophical / aesthetic point of view, and do I actually enjoy using the technique?

As mentioned above, I don’t really feel great about using Unique Rectangles philosophically. But, once I learned how to use them, it turned out that they were kind of fun! So that helped me get over my misgivings: not only did it unlock a different level of puzzle, I ended up enjoying solving them.

And there were actually some other techniques where those feelings were flipped. From an aesthetic point of view, I really like the Y-Wing technique: it leads to a nice pure form of a proof by contradiction. And if I can spot one in a puzzle, then that’s great, I really enjoy that.

But spotting it requires finding a certain configuration of three different cells each of which has two legal numbers in a certain configuration. And, if you’ve got lots of cells in the puzzle with two possible numbers, then finding a triple that leads to a Y-Wing can take a lot of searching. So it was pretty common for me to think I’d searched everywhere, to not find anything, then to give up and ask for a hint, and for the game to point out a Y-Wing that I missed.

So that’s one question that the game raised: what kinds of techniques do I want to use, either from a point of view of propriety or from a point of view of enjoyment? But I also noticed something else while playing the game: I’d use techniques that weren’t on the game’s list at all.

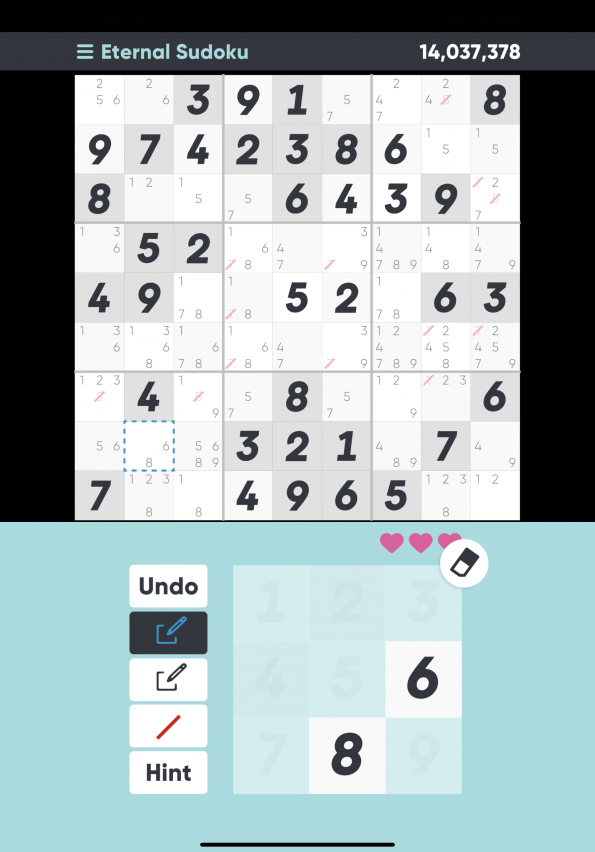

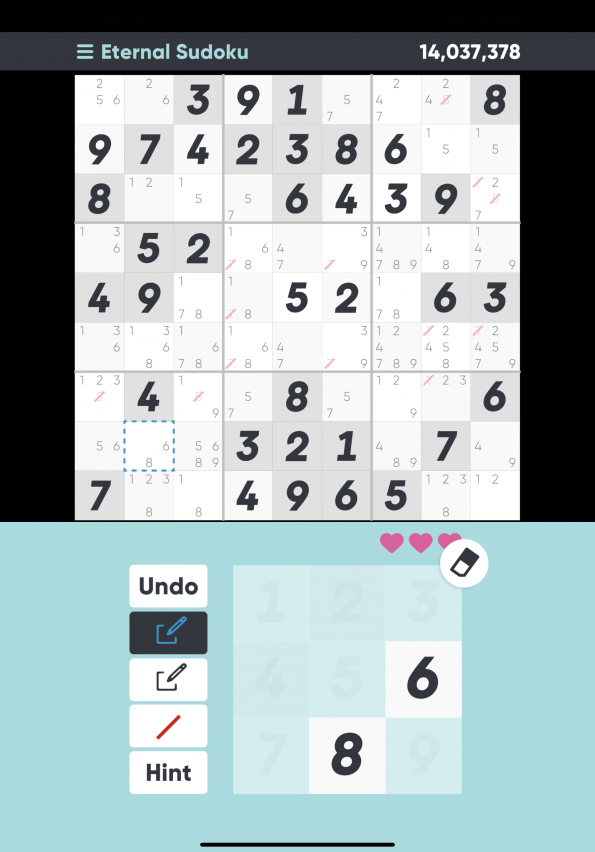

Consider this puzzle:

If you imagine entering a 6 in the blue cell, then the cell at the top of that column has to be a 2, the cell beneath it has to be a 1, and the cell to the right of that one has to be a 5. Whereas if you instead put an 8 in the blue cell, then the cell diagonally beneath it to the right has to be a 1, and the cell at the top of that column has to be a 5. That’s the same cell that we ended up at before, so we’ve shown that, whether we start from a 6 or an 8, we end up with a 5 in that one cell, so we can go fill that in.

This is a lot like a Y-Wing, it just involves an extra step along one of the paths. And Good Sudoku will never give you a puzzle that requires you do this kind of multi-step deduction: every technique in the game is of the form “if these cells satisfy these properties then these other cells either can’t have or must have this number”.

I went along with that for a long time: trying to use the official techniques until I got stuck, then asking for a hint. And then, usually, being annoyed at myself for missing something in my search, but sometimes I learned something, even beyond my initial exposure to new techniques. (In particular, I wouldn’t have understood the depth that’s hidden behind the terms “Unique Rectangle” and “Avoidable Rectangle” if I hadn’t seen multiple variants in hints.) So I’m glad that I took that approach.

But, at some point, I got tired of doing that. Good Sudoku lets you mark individual numbers on a cell in blue, so, for a lark, I picked a cell with only two choices that seemed kind of central, marked one of the choices with blue, and started following a chain of deductions, marking more numbers with blue. And, ten or fifteen marks later, I had the same number in two cells that could see each other, so I knew my initial choice was wrong; I filled in the other choice, and had the whole puzzle solved in short order.

It turns out that that wasn’t a fluke: pretty reliably, once I got to where I was stuck, I could make progress by trying something out and seeing how things went. And it was more fun than banging my head against pattern matching: I was able to succeed without asking for hints, and also I was spending more of my time doing something active instead of staring at things and hoping I’d see a pattern.

This is something I’ve seen in other puzzle forms that I enjoy: I spend most of my time just narrowing down possibilities by finding and applying patterns, but it’s honestly sometimes a bit of a disappointment if that’s all that I’m doing. There’s something pleasant about going as far as I can through that route, feeling stuck, and then saying “this area looks funny, let me try something out there” and breaking through that way.

That approach isn’t what Good Sudoku is focused on, though. I’m actually curious what a Sudoku game would be like that did focus on that sort of exploration of the possibility space: fewer tools for pattern matching, more tools for trying out a hypothesis, and backtracking if that hypothesis didn’t pan out? But Good Sudoku provides enough tools: having two colors to mark numbers with plus an undo button is really all you need.

And, of course, I don’t want every game to try to please you in every way. Good Sudoku is very good at the approach that it takes, teaching skills in a way that I’ve literally never seen in software before. That alone would be enough; the fact that it then pushed me beyond its limits to teach me something about aesthetics and possibilities is a bonus.

Posts

Posts